last update: Friday, April 24, 2020

URLs for A “Pre-History” & a Foundational Context:

- This post is the main post on a Pre-History & a Foundational context of the Field of AI. In this post a narrative is constructed surrounding the “Pre-History”. It links with the following posts:

- This post is a first and very short linking with on Literature, Mythology & Arts as one of the foundational contexts of the Field of AI

- The second part in the contextualization is the post touching on a few attributes from Philosophy, Psychology and Linguistics

- Following one can read about very few attributes picked up on from Control Theory as contextualizing to the Field of AI

- Cognitive Science is the fourth field that is mapped with the Field of AI.

- Mathematics & Statistics is in this writing the sixth area associated as a context to the Field of AI

- Other fields contextualizing the Field of AI are being considered (e.g. Data Science & Statistics, Economy, Engineering fields)

The Field of AI: A “Pre-History”.

A “pre-history” and a foundational context of Artificial Intelligence can arguably by traced back to a number of events in the past as well as to a number of academic fields of study. In this post only a few have been handpicked.

This post will offer a very short “pre-history” while following posts will dig into individual academic fields that are believed to offer the historical and present-day context for the field of AI.

It is not too far-fetched to link the roots of AI, as the present-day field of study, with the human imagination of artificial creatures referred to as “automatons” (or what could be understood as predecessors to more complex robots).

While it will become clear here that the imaginary idea of automatons in China is remarkably older, it has been often claimed that the historic development towards the field of AI, as it is intellectually nurtured today, commenced more than 2000 years ago in Greece, with Aristotle and his formulation of the human thought activity known as “Logic”.

Presently, with logic, math and data one could make a machine appear to have some degree of “intelligence”. Note, it is rational to realize that the perception of an appearance does not mean the machine is intelligent. What’s more, it could be refreshing to consider that not all intelligent activity is (intended to be seen as) logical.

It’s fun, yet important, to add that to some extent, initial studies into logic could asynchronously be found in China’s history with the work by Mòzǐ (墨子), who conducted his philosophical reflections a bit more than 2400 years ago.

Coming back to the Ancient Greeks: besides their study of this mode of thinking, they also experimented with the creation of basic automatons.

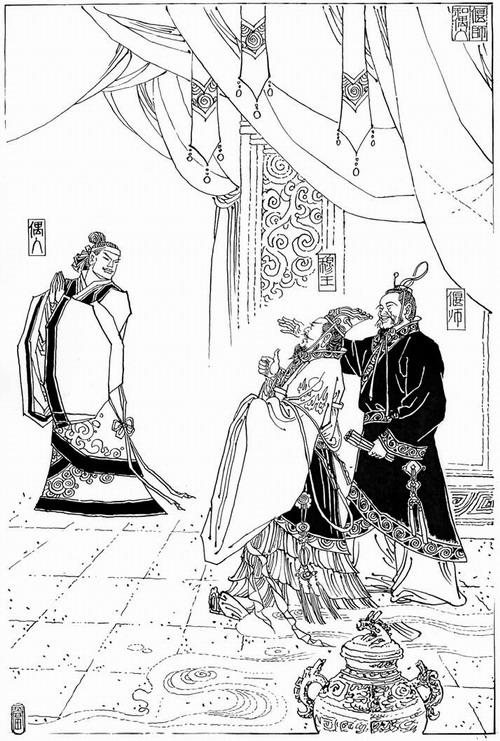

Automatons (i.e. self-operating yet artificial mechanical creatures) were likewise envisioned in China and some basic forms were created in its long history of science and technology.[1] An early mentioning can be found in, Volume 5 “The Questions of Tang” (汤问; 卷第五 湯問篇) of the Lièzǐ (列子)[2], an important historical Daoist text.

In this work there is mentioning of this kind of (imagined) technologies or “scientific illusions”.[3] The king in this story became upset by the appearance of intelligence and needed to be reassured that the automaton was only that, a machine …

Jumping forward to the year 1206, the Arabian inventor, Al-Jazari, supposedly designed the first programmable humanoid robot in the form of a boat, powered by water flow, and carrying four mechanical musicians. He wrote about it in his work entitled “The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices.”

It is believed that Leonardo Da Vinci was strongly influenced by his work.[4] Al-Jazari additionally designed clocks with water or candles. Some of these clocks could be considered programmable in a most basic sense.

One could argue that the further advances of the clock (around the 15th and 16th century) with its gear mechanisms, that were used in the creation of automatons as well, were detrimental to the earliest foundations, moving us in the direction of where we are exploring AI and (robotic) automation or autonomous vehicles today.

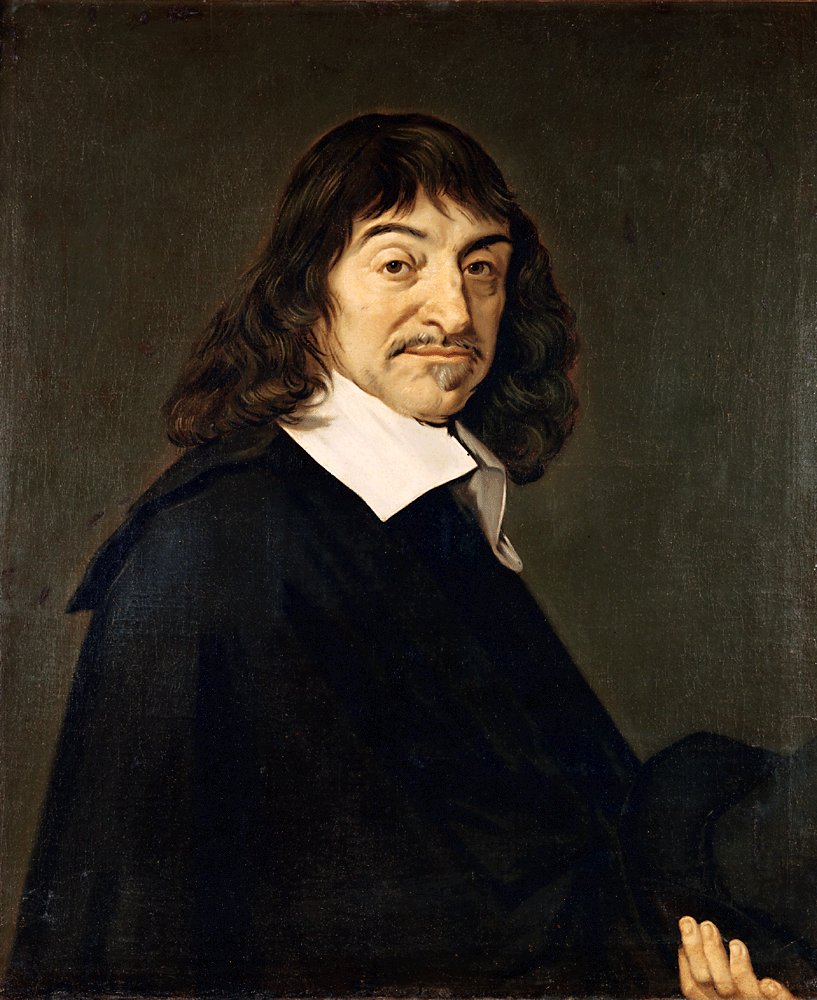

Between the 16th and the 18th centuries, automatons became more and more common. René Descartes, in 1637, considered thinking machines in his book entitled “Discourse on the Method of Reasoning“. In 1642, Pascal created the first mechanical digital calculating machine.

Between 1801 and 1805 the first programmable machine was invented by Joseph-Marie Jacquard. He was strongly influenced by Jacques de Vaucanson with his work on automated looms and automata. Joseph-Marie’s loom was not even close to a computer as we know it today. It was a programmable loom with punched paper cards that automated the action of the textile making by the loom. What is important here was the system with cards (the punched card mechanism) that influenced the technique used to develop the first programmable computers.

In the first half of the 1800s, the Belgian mathematician, Pierre François Verhulst discovered the logistic function (e.g. the sigmoid function),[1] which will turn out to be quintessential in the early-day developments of Artificial Neural Networks and specifically those called “perceptrons” with a threshold function, that is hence used to activate the output of a signal, and which operate in a more analog rather than digital manner, mimicking the biological brain’s neurons. It should be noted that present-day developments in this area do not only prefer the sigmoid function and might even prefer other activation functions instead.

[1] Bacaër, N. (2011). Verhulst and the logistic equation (1838). A Short History of Mathematical Population Dynamics. London: Springer. pp. 35–39. Information retrieved from https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-0-85729-115-8_6#citeas and from mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Verhulst.html

In 1936 Alan Turing proposed his Turing Machine. The Universal Turing Machine is accepted as the origin of the idea of a stored-program computer. This would later, in 1946, be used by John von Neumann for his “Electronic Computing Instrument“.[6] Around that same time the first general purpose computers started to be invented and designed. With these last events we could somewhat artificially and arbitrarily claim the departure from “pre-history” into the start of the (recent) history of AI.

As for fields of study that have laid some “pre-historical” foundations for AI research and development, which continue to be enriched by AI or that enrich the field of AI, there are arguably a number of them. A few will be explored in following posts. The first posts will touch on a few hints of Literature, Mythology and the Arts.

[1] Needham, J. (1991). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 2, History of Scientific Thought. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University.

[2] Liè Yǔkòu (列圄寇 / 列禦寇). (5th Century BCE). 列子 (Lièzǐ). Retrieved on March 5, 2020 from https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/7341/pg7341-images.html and 卷第五 湯問篇 from https://chinesenotes.com/liezi/liezi005.html and an English translation (not the latest) from https://archive.org/details/taoistteachings00liehuoft/page/n6/mode/2up

[3] Zhāng, Z. (张 朝 阳). ( November 2005). “Allegories in ‘The Book of Master Liè’ and the Ancient Robots”. Online: Journal of Heilongjiang College of Education. Vol.24 #6. Retrieved March 5, 2020 from https://wenku.baidu.com/view/b178f219f18583d049645952.html

[4] McKenna, A. (September 26, 2013). Al-Jazarī Arab inventor. In The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Online: Encyclopaedia Britannica Retrieved on March 25, 2020 from https://www.britannica.com/biography/al-Jazari AND:

Al-Jazarī, Ismail al-Razzāz; Translated & annotated by Donald R. Hill. (1206). The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: D. Reidel Publishing Company. Online Retrieved on March 25, 2020 from https://archive.org/details/TheBookOfKnowledgeOfIngeniousMechanicalDevices/mode/2up

[5] Bacaër, N. (2011). Verhulst and the logistic equation (1838). A Short History of Mathematical Population Dynamics. London: Springer. pp. 35–39. Information retrieved from https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-0-85729-115-8_6#citeas and from mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Verhulst.html

[6] Davis, M. (2018). The Universal Computer: the road from Leibniz to Turing. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group